By Jonathan Markovitz

SAN DIEGO – When 42-year-old Fridoon Rawshan Nehad was shot and killed by a San Diego police officer four years ago, his grieving family wanted answers. But California’s secretive public records laws protecting officer misconduct prevented them from getting the information they wanted and deserved.

Like many families across the state, Nehad’s relatives were left to wonder what exactly happened and who was responsible. Too often, California families are not told whether the officers who killed, injured or sexually assaulted their relatives will ever have to answer for their actions.

Under “The Right to Know Act” (SB 1421), a new law that took effect on Jan. 1, 2019, this is supposed to change.

SB 1421 was written in the wake of a series of high-profile police killings of unarmed civilians, especially black men and boys, and most notably Stephon Clark in California’s capital city. The 22-year-old Sacramento man was in his grandmother’s backyard, unarmed, when two officers opened fire killing him.

This deadly shooting was captured on video and sparked widespread protests.

In San Diego, Nehad was unarmed and experiencing a mental health crisis shortly after midnight on April 30, 2015, when a San Diego police officer shot and killed him. The officer opened fire just seconds after encountering Nehad in an alleyway in the Midway District.

Nehad’s parents had to sue to find out that the police officer was never disciplined for his actions. Their lawsuit revealed the officer was never interviewed by SDPD internal affairs nor anyone in the district attorney’s office before former District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis decided not to prosecute him.

Similarly, Sacramento authorities initially declined to provide information to Stephon Clark’s family about the investigation into his death.

“The Right to Know Act” is intended to prevent the kind of police stonewalling these families experienced. It requires disclosure of records of investigation and discipline related to police shootings and other serious uses of force, as well as disclosure of records related to sustained findings of sexual assault and dishonesty by police officers.

SB 1421 gives the public the right to know when there are serious police misconduct problems and whether law enforcement agencies are addressing these problems appropriately. It provides police transparency and accountability that have been missing in California for decades.

SB 1421 became a law despite opposition from police unions, who fought against it tooth and nail. And now, these same unions have launched a series of lawsuits up and down the state to try to undermine this important new law. Their goal is to narrow its scope and dilute its impact by making sure the law applies only to police conduct records created since January 1, 2019.

In short, police unions want to keep all past misconduct shrouded in secrecy.

Although the unions’ lawsuits were filed against government entities, the ACLU, media organizations and victims’ families successfully petitioned to participate in litigation to ensure the courts hear from impacted family members and advocates who are determined to defend the new law.

In San Diego, the ACLU Foundation of San Diego & Imperial Counties (ACLUF-SDIC) intervened in a lawsuit filed by a group of police unions seeking to prevent the release of local misconduct records. As in the other suits, the unions argued that SB 1421 did not cover records created before the law took effect.

On March 1, the ACLUF-SDIC Legal Director David Loy argued in court that the agencies must comply with SB 1421 and disclose the records regardless of when they were created.

San Diego County Superior Court Judge Eddie C. Sturgeon issued a ruling on the same day, siding with the ACLU, several local news outlets and victims’ families.

After the hearing, Loy said: “This ruling is a victory for transparency and accountability. Families and the public have a right to know if their local police departments are holding officers accountable when they violate the law or department rules – or if they are putting them back on the streets to do more harm.”

The ACLU believes that meaningful oversight of police conduct is weakened when the public is prevented from learning the most basic information about internal investigations and disciplinary proceedings.

When debating the law, state legislators rightfully pointed out that concealing an officer’s violations of civilians’ rights or inquiries into deadly use of force incidents undercut people’s faith in the legitimacy of law enforcement. This loss of public trust endangers public safety and makes it harder for tens of thousands of hardworking peace officers to do their jobs.

Californians must be provided with the information necessary to understand how government agencies have responded to police misconduct, regardless of when it occurred. Toward this end, the ACLU will continue fighting for the people’s right to know.

Jonathan Markovitz is a staff attorney for the ACLU Foundation of San Diego & Imperial Counties.

Concealing police misconduct undermines public trust

Related Issues

Related content

Lagleva et al. v. Doyle

October 14, 2021

The C.R.I.S.E.S. Act (AB 2054)

August 10, 2020

P.R.O.M.I.S.E Act (AB 1007)

August 10, 2020

What to do if you're stopped by the police or law enforcement .

August 9, 2020Advocacy

August 5, 2020

Kenneth Ross Jr. Decertification Act (SB 731)

June 30, 2020

ACLU: Authorities Must Develop COVID-19 Prevention and Management...

March 12, 2020

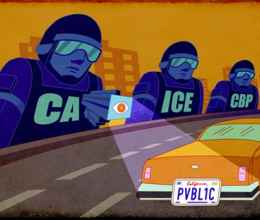

ACLU: San Diego Police and Sheriff’s Department data shows...

January 21, 2020