1933

The American Civil Liberties Union began working in San Diego and Imperial counties in 1933, when our founder, Helen Marston established the "San Diego ACLU Committee." As a board member of the relatively new ACLU in Los Angeles, Marston hoped to affirm civil liberties for those least recognized by the courts.

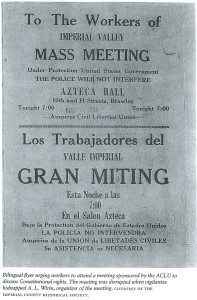

1934

While supporting Imperial Valley farm workers' right to strike and assemble, ACLU representatives—including Helen Marston—were chased and assaulted by vigilante mobs. Famed ACLU attorney A.L. Wirin secured a court order protecting the workers' right to meet unmolested. But before the meeting, Wirin was kidnapped, beaten, and left for dead in the desert. Marston contacted Franklin D. Roosevelt and others, and a federal investigation followed that substantiated the ACLU's charges of abuse by farm owners, vigilantes, and the police.

1942

The national ACLU lobbied hard against the internment of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese American citizens when Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering the evacuation of Japanese aliens and "non-aliens" from the West Coast following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. On May 19, 1942, San Diegans of Japanese descent were required to report to the Santa Fe Depot, where they were forced to board trains that were closed and guarded. They were sent to a detention center at the Santa Ana Race Track, and then to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona.

Over the next two years, the national ACLU, and its offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle took on cases challenging the internment: Hirabayashi, Korematsu, Yasui, Wakayama, and Endo.

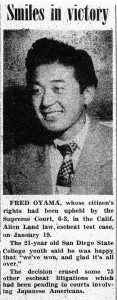

1944

A Chula Vista family that was forced to evacuate to Utah learned that its home and land had been seized by California under the state's "Alien Land Act," which forbade "aliens ineligible for citizenship" [non-whites] to own land.With ACLU attorney A.L. Wirin, Kajiro Oyama and his son, Fred, challenged the Act in Oyama v. California, losing in the lower courts, but winning a landmark decision in the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirin said that the Oyama (and another case, Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission) were the most important cases of his career "because they were able to establish principles which were the forerunners of the U.S. Supreme Court cases involving Negroes [sic] and affording them the rights to equal treatment and equal protection under the law."

1946

The San Diego School Board required loyalty oaths from members of community groups seeking to hold meetings in public buildings. Their stated intention was to keep "subversive" organizations from using the school buildings.

The San Diego ACLU Committee filed a lawsuit challenging the oaths in Danskin v. San Diego Unified School District. The ACLU view prevailed with the Supreme Court of California, with the majority opinion by Justice Roger Traynor stating that the government, while needing to be vigilant on behalf of the safety of its citizens, "must distinguish, however, between speech, no matter how unorthodox, that remains on a theoretical plane, and speech, no matter how skillfully intoned, that creates a clear and present danger to the community."

1955

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court banned segregation in public schools in the historic Brown v. Board of Education. Here in San Diego the next year, attorney A.L. Wirin addressed a technical subterfuge following the Brown decision in Romero v. Weakley, challenging the district that, like many other school districts, skirted the Brown ruling by classifying Mexicans and other Latinos as "White" for desegregation purposes—while continuing to assign Anglo children to all-white schools. In so doing, the two largest minority school populations—black and brown students—were essentially excluded from superior facilities, staffing, and resources, that Anglo children were provided.

Wirin won the desgregation fight in El Centro on behalf of 22 African American and 40 Mexican students, though the court abstained and the school district settled the case. Because the case settled, it would take Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District in 1970 to end the technical segregation loophole.

1960

In a rare Saturday session, a San Diego Superior Court judge ruled against the San Diego Unified School Board, when ACLU lawyers Irwin Gostin and Lou Katz challenged the board's decision to bar folk singer Pete Seeger from playing a concert at Hoover High School. The board was insisting that Seeger sign a non-communist loyalty oath before he could perform. Seeger was already under indictment for refusing to respond to a Joseph McCarthy congressional panel about his politics and (brief) membership in the Communist Party.

The oath the Board wanted him to sign read in part, "The undersigned states that, to the best of his knowledge, the school property...will not be used for the commission of any act intended to further any program or movement the purpose of which is to accomplish the overthrow of the government of the United States by force, violence, or other unlawful means...and is not a Communist-action organization or a Communist-front organization required by law to be registered with the attorney general of the United States. This statement is made under the penalties of perjury."

[As a codicil, the San Diego School Board apologized to Seeger in 2009, just shy of 50 years after this incident. Pete Seeger, always a peacemaker, supplied us with a written statement in reaction to the Board's apology: "It is a measure of justice that our right to freedom of expression and association has been vindicated."

Pete Seeger died at the age of 94 in 2014.]

1967

Thirteen years after the U.S. Supreme Court banned school segregation, the ACLU argued a class-action suit in San Diego, Carlin v. Board of Education, claiming that the city's schools were still segregated and that white children were favored academically.

The historic lawsuit resulted in an integration order and court monitoring that continued until 1998. The decision—nine years in the making—required the school district to develop programs to integrate its schools, though the district could determine what methods to use. The district developed voluntary busing and magnet schools.

1977

With attorney Alex Landon, the ACLU successfully challenged San Diego's severely overcrowded jails in Hudler v. Duffy and Armstrong v. Board of Supervisors, resulting in the imposition of population caps to prevent overcrowding that continue to this day. Throughout subsequent legal challenges over the decades, the ACLU either won outright or reached favorable settlements in a variety of overcrowding cases in 6 adult jails and, in 1992, in Juvenile Hall. In that case, a Superior Court judged ruled that conditions at the Hall "so violate basic constitutional rights that just being there amounts to punishment," even though it holds young children not charged with a crime.

1977

ACLU attorney Robert Lynn represented Edward Lawson in a federal court challenge, Kolender v. Lawson, to a California law and San Diego Police Department practice that allowed police to stop people and require "credible" identification. Lawson, who had long dreadlocks but was described in court documents as "a law-abiding black man," was frequently subjected to police questioning and harassment when he walked in white neighborhoods. The ACLU challenged the law requiring "persons who loiter or wander on the streets to provide a 'credible and reliable' identification and to account for their presence when requested by a peace officer."

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where a 7-2 majority held that the standard was unconstitutionally vague.

1987

Legendary San Diego attorney Tom Homann, on behalf of the ACLU, in Leyland v. Orr, challenged the discharge of a transgender man from the U.S. Air Force who had been deemed "psychologically unsuitable and physically unfit because of transsexualism and completion of sex change surgery." The Ninth Circuit Court ruled against Jane Anne Leyland, citing the physician's opinion as a reason. Dr. Donald Novicki, a urology consultant to the Air Force surgeon general, said that it was risky to send a transgender person to "remote geographic areas," saying it "would be equivalent to placing an individual with known coronary artery disease in a remote location without readily available coronary care."

[Secretary of Defense Ash Carter said in 2015 that the Department of Defense would allow transgender individuals to serve in the military in early 2016, giving military services time to prepare for integration. In memoriam, thank you, Tom Homann!]

1990

In our own version of Dickens' Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, the ACLU continues to seek a constitutional solution to a long-standing controversy involving the Mt. Soledad Cross, a Christian cross sitting on top of La Jolla's highest hill, and on public land (first a city-owned park, later "taken" by the federal government) in Jewish War Veterans of the USA v. Hagel. The cross has served as the site for Christian religious observances, and is known by many San Diegans as "The Easter Cross." When the cross was dedicated on Easter Sunday 1954 to "Our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ," it was declared a tribute to veterans of WWI, WWII, and the Korean Conflict, but no plaque was installed until two years after a lawsuit was initiated by a Vietnam veteran and self-described humanist and atheist, Phillip Paulson, claiming the religious symbol's presence on public land violated provisions of the U.S. and California constitutions prohibiting the government from favoring one religioin over another. It wasn't until 2000 that an American flag and a series of granite walls displaying individual veterans' plaques were added.

The ACLU fully supports the rights of Christians and people of all faiths to actively practice their religions freely, without government constraint. We firmly believe that the right of religious expression in the public sphere is a core principle of our Constitution. We also believe that it is people of faith—not governments, legislators, or political majorities—who should be responsible for expressing religious beliefs.

Read a timeline of the Mt. Soledad Controversy, which still is in litigation. Over the years, the ACLU participated in this case with Paulson's original attorney, James McElroy, who continues to seek a constitutionally sound resolution to this issue.

1992

Youngsters might have trouble believing this, but until the ACLU successfully argued the point in a friend-of-the-court brief in U.S. v. DeGross, women could be systematically excluded from a jury through peremptory challenges. DeGross established that equal protection principles prohibit a party from peremptorily striking potential jurors on the basis of their gender.

[A prior case—though not San Diego related—only decided in 1986 by the U.S. Supreme Court, Batson v. Kentucky, established that peremptory challenges could not be used to exclude jurors solely based on their race.]

1996

The San Diego ACLU sued (NOW v. City of San Diego and Republican National Committee) when the city, at the request of the Republican National Committee, vetoed a proposed protest site across the street from the 1996 GOP National Convention and instead chose a remote location out of sight of the convention hall. City officials called the location, at least 3 blocks from the convention site, a "compromise." Said the ACLU's managing attorney, Jordan Budd, "The City calls the new site a 'compromise.' The only thing that has been compromised is the First Amendment. The RNC has no right to demand that the City of San Diego offer up the constitutional rights of its citizens as a price tag for hosting the Republican National Convention."

In one of the nation's first "free speech zone" cases, a district court ruled that protesters, representing more than 60 groups, had a First Amendment right to be within sight and sound of the convention. After continued back-and-forths, The RNC ultimately settled, and agreed to pay the ACLU's attorneys' fees.

2000

In May 2000, the ACLU and other civil rights organizations filed Williams v. State of California against the state of California because of the terrible conditions in many of its public schools. The situation was most acute in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. We argued that the State's failure to provide these bare minimum necessities to all public school students violated the state constitution and federal requirements that all students be given equal access to public education without regard to race, color, or national origin.

In August 2004, the parties announced a settlement, requiring that all students have books, that their schools be safe and clean, and that the state take steps to make sure that students have qualified teachers. $1 billion was provided to accomplish these goals.

The ACLU of California continues to monitor compliance. Please contact us if you feel your child's school does not meet the Williams requirements.

2000

In July 2000, the ACLU challenged San Diego County's "Project 100%" in Sanchez v. County of San Diego, run by San Diego County’s District Attorney’s Office, in which virtually everyone who applies for California’s public assistance program must consent to a “home visit” by a Public Assistance Investigator before cash benefits can be issued. San Diego County is the only county in the nation with such a program.

The case made its way to the highest appeals court in California, but unfortunately, the program survived the legal challenge based on a bizarre ruling that the "visits" are not searches and are voluntary. However, applicants who don't agree to the searches are disqualified from eligibility. A judge writing for the minority said that upholding Project 100% "strikes an unprecedented blow at the core of Fourth Amendment protections," and called the case "an assault on the poor."

The ACLU is continuing to investigate P100 to see if the project should be challenged again in the courts.

2000

In another long-running lawsuit, Barnes-Wallace v. City of San Diego, the ACLU asked the City of San Diego to end its taxpayer subsidy of discrimination by the Boy Scouts, who explicitly excluded the children of gay and agnostic parents. The City of San Diego gave exclusive use of 18 acres of prime park property in city-owned Balboa Park for $1 per year since 1957, and free use of an aquatic facility on city-owned Fiesta Island in Mission Bay through preferential leases.

The lawsuit was filed after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that discriminating against gays is so essential to the mission of the Boy Scouts that the organization could invoke its First Amendment rights of free expression and association to protect its right to discriminate. That didn't sit well with us. We believe that the leases violated the Equal Protection Clause “by endorsing, supporting, and promoting defendants’ discrimination based on sexual orientation.”

A District Court agreed with us, but when the case was appealed to the Ninth Circuit, a panel reversed the decision in favor of the Boy Scouts. “There is no evidence the city’s purpose in leasing the subject properties to the Boy Scouts was to advance religion, and there is abundant evidence that its purpose was to provide facilities and services for youth activities,” wrote the court.

In 2013, the plaintiffs decided not to appeal a circuit court ruling in favor of the Boy Scouts, ending the suit. Although unsuccessful, the district court suggested that the claim was reasonable, and ultimately led to successful challenges to such discrimination as in cases like Obergfell v. Hodges (2015).

2006

Along with our national office and the other two ACLU offices in California, the San Diego ACLU filed lawsuits against telecom giants AT&T and Verizon. We hoped to stop them from helping the Bush Administration's program of intercepting phone calls and emails from Americans and suspected foreign terrorists by providing the National Security Agency with the personal phone records of millions of Californians. Since September 11, the phone companies had been providing the NSA with customers' records, without any sort of and without the customers’ knowledge. [Fans of "The Good Wife" will have some sense of what this spying looks like, at least as imagined by the writers at CBS.]

In all, about 40 lawsuits were filed nationwide against telecommunications companies; they were consolidated before the federal district court in San Francisco. In June 2009, the federal court dismissed all the lawsuits, relying on the immunity provision granted by Congress last year to the telecommunications companies charged with participating in the NSA spying.

2006

In an unexpected but welcome reversal, the city of Escondido agreed to settle a lawsuit, Garrett v. City of Escondido brought against it by the ACLU and a coalition of civil rights organizations challenging a controversial city ordinance that banned renting apartments to undocumented immigrants. The settlement, which called for a permanent injunction against enforcement of the ordinance, came after a federal judge granted a temporary restraining order. Judge John Houston said the ordinance raised "serious questions" about a number of federal and state issues, and expressed concern about tenants being evicted without due process or a public hearing.

In October 2007, California became the first state to prohibit anti-immigrant rental ordinances. Beyond noting that such measures are unconstitutional because immigration matters are exclusively the domain of the federal government, courts have found such measures to have the potentially insidious effect of causing housing discrimination based on race or a person's perception of a prospective tenant's background. The California law will help prevent the denial of housing to people based on their race, ethnicity, or national origin, or whether they simply look or sound foreign.